Political Report

In Louisiana, Sheriff Elections Will Shape ICE’s Reach

“They’re trying to send Hispanics to Mexico or Honduras and put Black men in jail,” said one candidate regarding prevailing practices. “The United States is made for everybody.”

“They’re trying to send Hispanics to Mexico or Honduras and put Black men in jail,” said one candidate regarding prevailing practices. “The United States is made for everybody.”

The Ascension Parish sheriff’s department detained a U.S. citizen as part of an immigration hold for four days despite a court order that he be released, according to a lawsuit by the ACLU of Louisiana. The ACLU alleges that this is part of a systematic policy to target Latinx individuals. Sheriff Bobby Webre, who was not yet in office during these specific events, told The Advocate that he would mount a “rigorous defense” of his department.

Moses Black Jr., however, takes issue with current practices. He is challenging Webre in the Oct. 12 sheriff’s election.

“The ACLU is doing the right thing bringing this to light,” he told the Appeal: Political Report this week. Local authorities are participating in a nationwide “all-out war on Hispanics,” he said, because “they can get away with it.” Webre’s office did not answer a request for comment on the ACLU’s allegations; Byron Hill, the third candidate in the race, also did not respond.

Louisiana will hold 63 elections for sheriff this fall. These could impact the reach of the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), as well as the scale of immigration enforcement and detention in the state.

Sheriffs nationwide have the authority to enter into various partnerships with ICE, both formal and informal. In Louisiana, many have taken full advantage over the past year to help the federal agency identify or incarcerate undocumented immigrants.

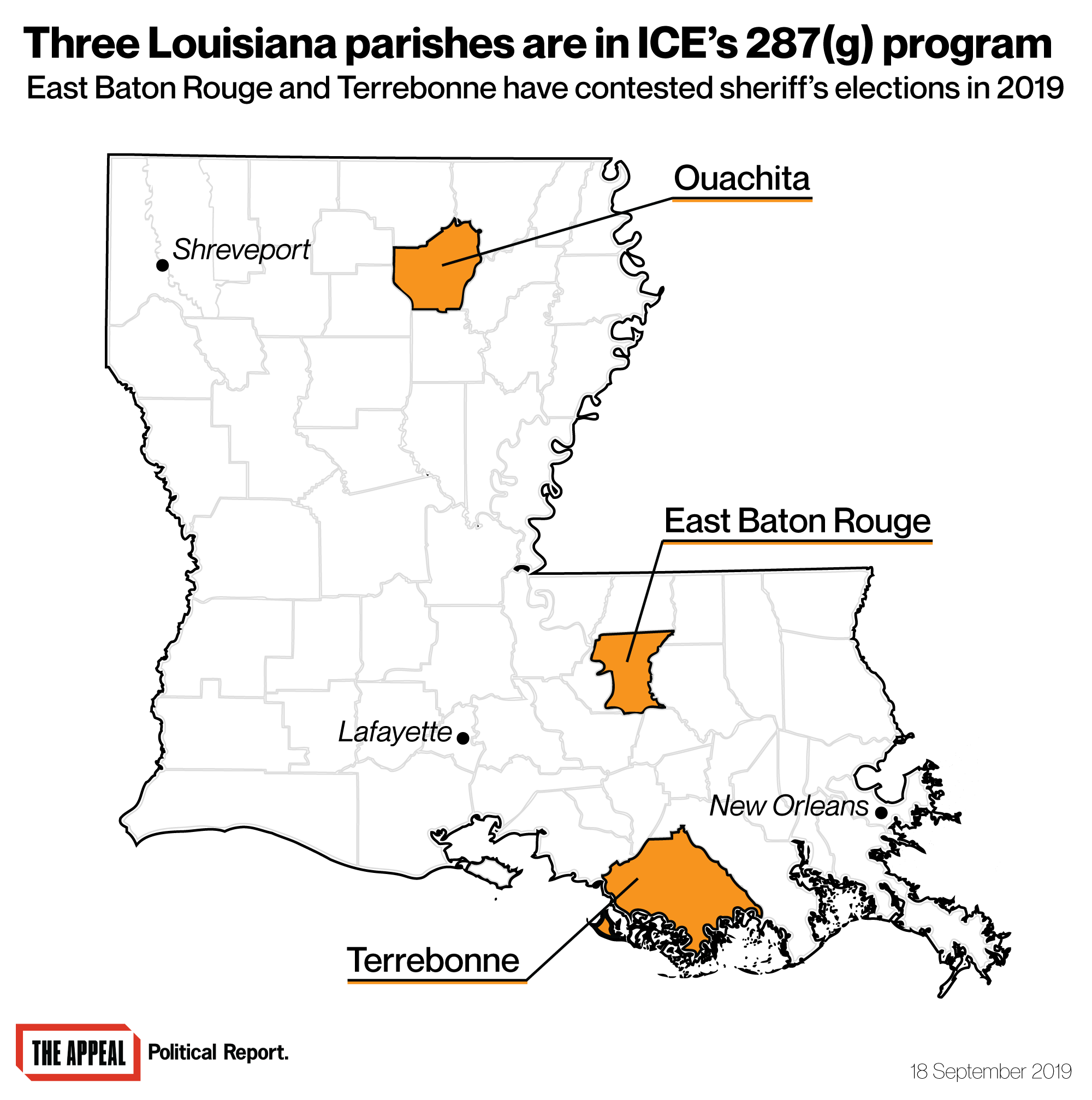

As Louisiana’s incarceration rate plunged in recent years, local agencies have rapidly entered in new contracts to rent now-vacant jail space to ICE, considerably expanding the federal agency’s capacity to detain immigrants. In addition, three sheriff’s departments have now joined ICE’s 287(g) program (two of them this year), which authorizes local deputies to act as federal immigration agents.

“This is a crisis happening in our own backyards, betraying the state’s commitment to decarceration and exposing thousands of immigrants and asylum seekers to brutal and dehumanizing conditions,” Alanah Odoms Hebert, executive director of the ACLU of Louisiana, told the Political Report. Investigations have found that people detained by ICE in the state are held in poor conditions.

Black, the sheriff candidate, faults the underlying racial pattern in the resilience of incarceration, and links amplified immigration enforcement to the criminal legal system’s disparate impact on African Americans. “I see Blacks who go to jail for lower offenses, and what they’re trying to do to Hispanics who come to the United States to make a better life for themselves and their families—I see that right now the government is trying to prevent that,” he said, adding that part of his platform is to reduce arrests by issuing more summons instead. “They’re trying to send Hispanics to Mexico or Honduras and put Black men in jail. The United States is made for everybody.”

“It’s a business for them,” he added. ICE pays counties more money to detain an immigrant than the state pays them to incarcerate someone with a criminal conviction, according to the Times-Picayune.

The sheriff’s elections this year offer a platform for immigrants’ rights advocates to call these policies into question. There is an election in every parish except Orleans (New Orleans), which is on a different schedule.

“These sheriffs absolutely need to answer to voters about their role in this crisis that diverts resources away from other public safety priorities and makes everyone less safe,” Odoms Hebert said. She called on candidates to curb cooperation with ICE, starting with 287(g). “First it is vital that sheriffs reject the harmful 287(g) agreements that undermine public trust and weaken the effectiveness of local law enforcement. But much more broadly, local law enforcement needs to respect the rights of the people they’re sworn to serve: that means taking steps to combat racial profiling and racially-biased policing, and building greater trust with these communities.”

On 287(g), eyes are on East Baton Rouge

Three Louisiana parishes have joined the 287(g) program, which deputizes sheriffs’ deputies to research the immigration status of people they book in the parish jail and arrest those they suspect of being undocumented. Sheriffs have the power to terminate existing agreements.

The largest is East Baton Rouge, Louisiana’s most populous parish and also one of its least conservative as Hillary Clinton won it by 9 percentage points in the 2016 presidential race.

The Baton Rouge Immigrants’ Rights Coalition organized a rally last week demanding that the sheriff’s office terminate 287(g). Republican Sheriff Sid Gautreaux III renewed the contract earlier this year amid a significant increase in ICE arrests in the parish.

Dauda Sesay, a member of the Baton Rouge coalition and president of the Louisiana Association for Refugees and Immigrants, told the Political Report that the parish’s relationship with ICE causes fear among immigrant residents with whom he interacts, regardless of their status. “With the stress that comes with moving to a new land, and us refugees we have this trauma in us, and all of what is happening at the national level, and now we find out that the parish is using this policy to partner with ICE: all of this adds to the trauma, it adds to the fear,” he said. Sesay, who came to the United States as a refugee from Sierra Leone, is an advocate for refugee settlement.

He argued that people tend to not strictly differentiate between various agencies, so the sheriff’s policies color people’s perceptions of all local law enforcement, making it less likely for them to report crime or interact with police. “When you have that much fear in the community, public safety is at risk,” he said.

Stephanie Dugas Braswell, an organizer with Indivisible Louisiana Capitol Region, a group that helped organize last week’s rally, echoed Sesay’s point. “How are people supposed to put their trust in that when their family and friends are being deported?” she asked. Gautreaux did not answer a request for comment on this criticism.

East Baton Rouge Parish’s membership in 287(g) is now at stake in this fall’s election.

Two Democratic challengers, Mark Milligan and Carlos Jean Jr., are challenging Gautreaux. If none of the three reaches 50 percent in October, the top two will move to a November runoff.

Each challenger told the Political Report that they oppose the 287(g) program. Milligan wrote in an email that 287(g) is a “violation of Civil rights, and civil liberties.” “We can not afford to harass potential ‘Legal Citizens’” while trying to identify “undocumented residents,” he added. He also said he would refuse to honor ICE requests that he detain people beyond their release date. Milligan said that these administrative requests, known as detainers, violate due process.

Jean said he “would discontinue the 287(g) program on my first day” because it is hurting “public safety and community trust.” Jean added that he would allow ICE to be stationed at the parish jail to check immigration status, however. He did not respond to a follow-up question on whether he would honor detainers.

Ouachita and Terrebonne are the two parishes that newly joined 287(g) earlier this year. Ouachita Parish Sheriff Jay Russell, who signed the agreement, is now running for reelection unopposed. The Terrebonne Parish sheriff who signed the contract, Jerry Larpenter, is not running. Of the seven people running to replace him, the only one who answered my request for comment, Bubba Bergeron, said he favored maintaining the 287(g) contract.

Other jurisdictions with 287(g) are holding contested elections this fall, including in New Jersey and in Virginia.

Detention contracts have multiplied

While sheriffs who have joined 287(g) actively help ICE identify people who may be undocumented, many sheriffs’ departments have struck separate detention agreements: They provide jail space for ICE to detain people it arrests elsewhere in exchange for payments.

These can be lucrative arrangements. Tim Lentz, a Republican who is challenging St. Tammany Parish Sheriff Randy Smith, a fellow Republican, told the Political Report that he takes issue with the financial considerations that are ballooning incarceration in his parish. Lentz said he wants to shrink the jail population. “I have campaigned on the promise of reducing the current size of our jail by half,” he said in a written message.

“Unfortunately the jail has become a for profit prison with over half of the population either state or federal inmates. The ICE contract will be closely reviewed after election.”

Still, these contracts have multiplied over the past year. “It seemed that Louisiana was ready to move away from its dependence on mass incarceration,” Jamila Johnson, a senior supervising attorney with the Southern Poverty Law Center, told The Advocate in May. “It’s disheartening to see that it continues to rely heavily on it through its switch to the mass incarceration of civil detainees.”

The Political Report contacted candidates in Allen, Concordia, Natchitoches, and St. Tammany parishes to ask whether they would keep or end the incumbent sheriffs’ existing partnerships; no one but Lentz responded.

Elsewhere still, sheriffs who have made deals with ICE are running for re-election unopposed. They include Jackson Parish’s Andy Brown and Bossier Parish’s Julian Whittington, who runs a jail where guards pepper-sprayed ICE detainees during a protest, Mother Jones reported.

And there are other opportunities for ICE to extend its reach. New sheriffs elected in any of the state’s parishes could apply for new contracts. “We are keeping a watchful eye around the state,” said Odoms Hebert, of the ACLU of Louisiana.

“We are just asking for a handshake, an opportunity,” Sesay said. “That opportunity is to not do things that make us feel unwelcome… A welcoming city is one in which diversity is celebrated to improve the opportunities of our residents. That is simple, that is all we ask for, and we want to extend that to the whole of the state of Louisiana.”