New Documents Reveal How ICE Mines Local Police Databases Across the Country

In cities across the country, Immigration and Customs Enforcement Homeland Security Investigations agents can mine local police reports using COPLINK, a data program little known outside law enforcement circles. While public records have revealed ICE’s access to this program in the past, new documents, obtained by the ACLU of Massachusetts and shared with The Appeal, offer the first […]

In cities across the country, Immigration and Customs Enforcement Homeland Security Investigations agents can mine local police reports using COPLINK, a data program little known outside law enforcement circles. While public records have revealed ICE’s access to this program in the past, new documents, obtained by the ACLU of Massachusetts and shared with The Appeal, offer the first up-close glimpse at how the program allows ICE to access millions of sensitive police records.

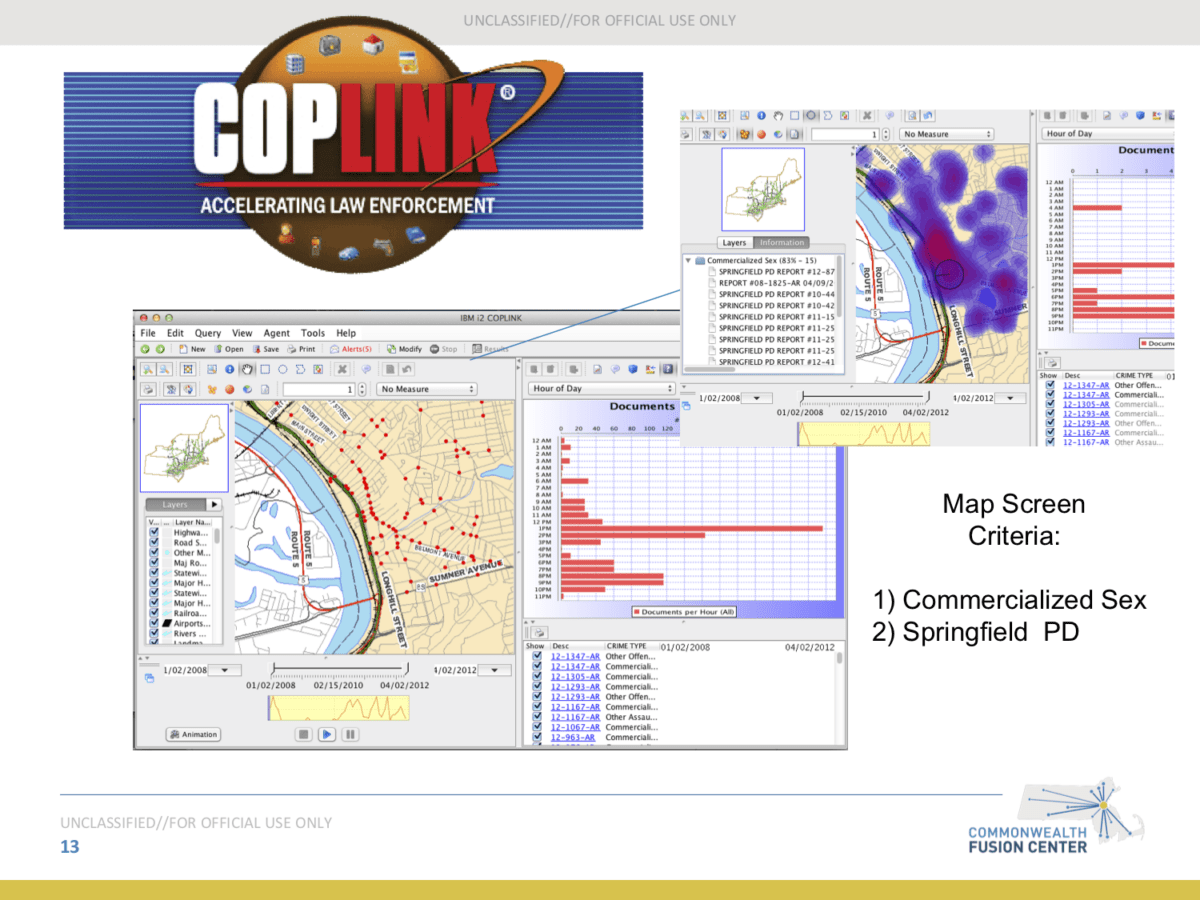

The software ingests local police databases, allowing users to map out people’s social networks and browse data that could include their countries of origin, license plate numbers, home addresses, alleged gang membership records, and more.

ICE HSI agents have direct access to the Massachusetts version of the COPLINK system, which receives records from Massachusetts’s Registry of Motor Vehicles, Board of Probation, and at least local 25 police agencies. As NPR has previously reported, ICE also has direct access to COPLINK-powered databases in other jurisdictions across the country, gathering data from dozens of police departments across Los Angeles County and Arizona.

Law enforcement officials and former ICE agents say the sharing of these databases and analytic tools helps ICE Homeland Security Investigations — the agency’s investigative arm — tackle serious crimes, like child pornographyand money laundering. But immigration advocates point out that ICE HSI agents are also involved in questionable immigration enforcement actions nationwide. These include investigations into undocumented residents accused of gang membership, sometimes based on flimsy evidence, and controversial workplace raids, which acting ICE chief Tom Homan recently announced plans to quadruple.

Earlier this month, at a slaughterhouse in Bean Station, Tennessee, ICE HSI agents carried out the largest workplace raid in over a decade, rounding upnearly 100 immigrants. Advocates say this raid signals a return to George W. Bush-era style workplace enforcement actions, which swept up hundreds of immigrants in towns like New Bedford, Massachusetts, over a decade ago.

Department of Homeland Security (DHS) data-sharing agreements obtained by The Appeal through the Freedom of Information Act make clear that ICE agents can access COPLINK “in the same manner” as local law enforcement for immigration enforcement purposes.

The constantly updated police records in COPLINK, arising from day-to-day police encounters, can be indispensable for ICE HSI agents, who often need to find addresses, cars, phone numbers, and associates that are not necessarily housed in federal or private sector databases, according to Massachusetts police and former ICE agents interviewed by The Appeal. They can help ICE officers conduct background research on employees before a workplace enforcement action or when planning logistics for a gang raid.

In a phone call with The Appeal, ICE spokesperson John Mohan declined to discuss ICE’s use of COPLINK. “We don’t talk about the techniques or tools [ICE agents] use,” said Mohan. The Appeal has since filed a Freedom of Information request for data on ICE agents’ querying of COPLINK databases across the country.

Notably, many of the major police departments that feed into COPLINK, and allow ICE direct access to their data, are situated in so-called “sanctuary” jurisdictions that have promised some measure of protection to undocumented immigrants. Los Angeles, San Gabriel, and Pasadena police, for example, feed into a Los Angeles County-wide COPLINK database, and Boston, Somerville, and Cambridge police feed into Massachusetts’s COPLINK regional database.

Kade Crockford, director of the ACLU of Massachusetts’s Technology for Liberty Program, argues that although it’s unclear whether sanctuary cities can legally withhold data from ICE, they should not actively help ICE agents by giving them direct access to local systems like COPLINK.

“By giving ICE and other federal agencies credentialed access to state and local law enforcement databases, communities are perhaps unintentionally endangering immigrants and other groups who may be targeted by the federal government,” Crockford said in a statement to The Appeal. “Data is toxic, and local communities must understand exactly what their police are collecting, how they are retaining it, and under what circumstances outside entities like ICE can access it.”

How the Program Works

COPLINK was initially developed by University of Arizona researchers in collaboration with the Tucson Police Department in 1998, as a way to share information between local police departments regionally. It has since spread to over 5,100 law enforcement jurisdictions throughout the United States and is now owned by the technology firm Forensic Logic.

ICE’s access to local COPLINK police databases has grown as well. In 2008, ICE signed data-sharing agreements with AZLINK, the COPLINK data hub in Arizona, and with IRIS, the COPLINK hub in Los Angeles County. It is unclear when ICE first formally gained access to Massachusetts police data through COPLINK, but a training roster obtained from the Massachusetts State Police listed numerous ICE agents and analysts next to dates, which correspond to COPLINK training sessions in 2015 and 2016.

In Massachusetts’s version of COPLINK, 25 police agencies across the state automatically feed almost all the data from their records management systems — including arrests, complaints, and citation reports — into COPLINK, according to the documents. Databases from another 13 police departments, in addition to the state’s Department of Correction, Parole Board, and sex offender registry, were being integrated into the program as of last year. According to Lieutenant Colonel Dermott Quinn, commander of the Massachusetts State Police’s Division of Investigative Services, the system also intakes accident reports, parking tickets, and field interview notes from local police departments.

ICE HSI agents have virtually unfettered access to COPLINK in Massachusetts. Similarly, ICE’s data-sharing agreements with Arizona’s AZLINK and the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department’s IRIS, both COPLINK systems, state explicitly that ICE agents are free to mine their data. In 2011, for example, Department of Homeland Security users, including ICE personnel, searched AZLINK, an Arizona regional data system that uses COPLINK software, thousands of times over a six-month period.

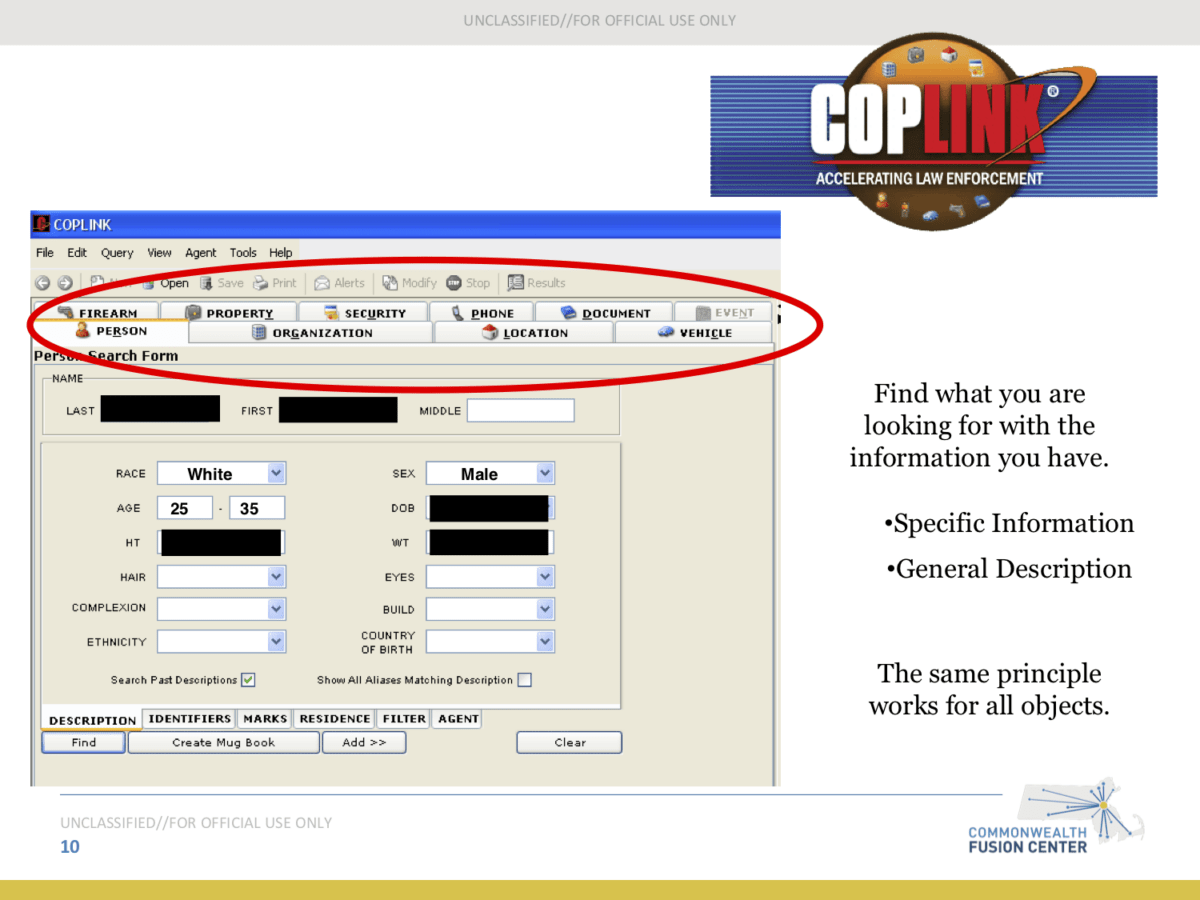

Drawing from this body of records, COPLINK allows users to search for individuals, organizations, and vehicles, among other things. These searches can be narrowed down using filters, such as a person’s race, hair color, eye color, complexion, ethnicity, and country of origin. The slide below also shows that users can search for people based on their residence and physical marks on their bodies.

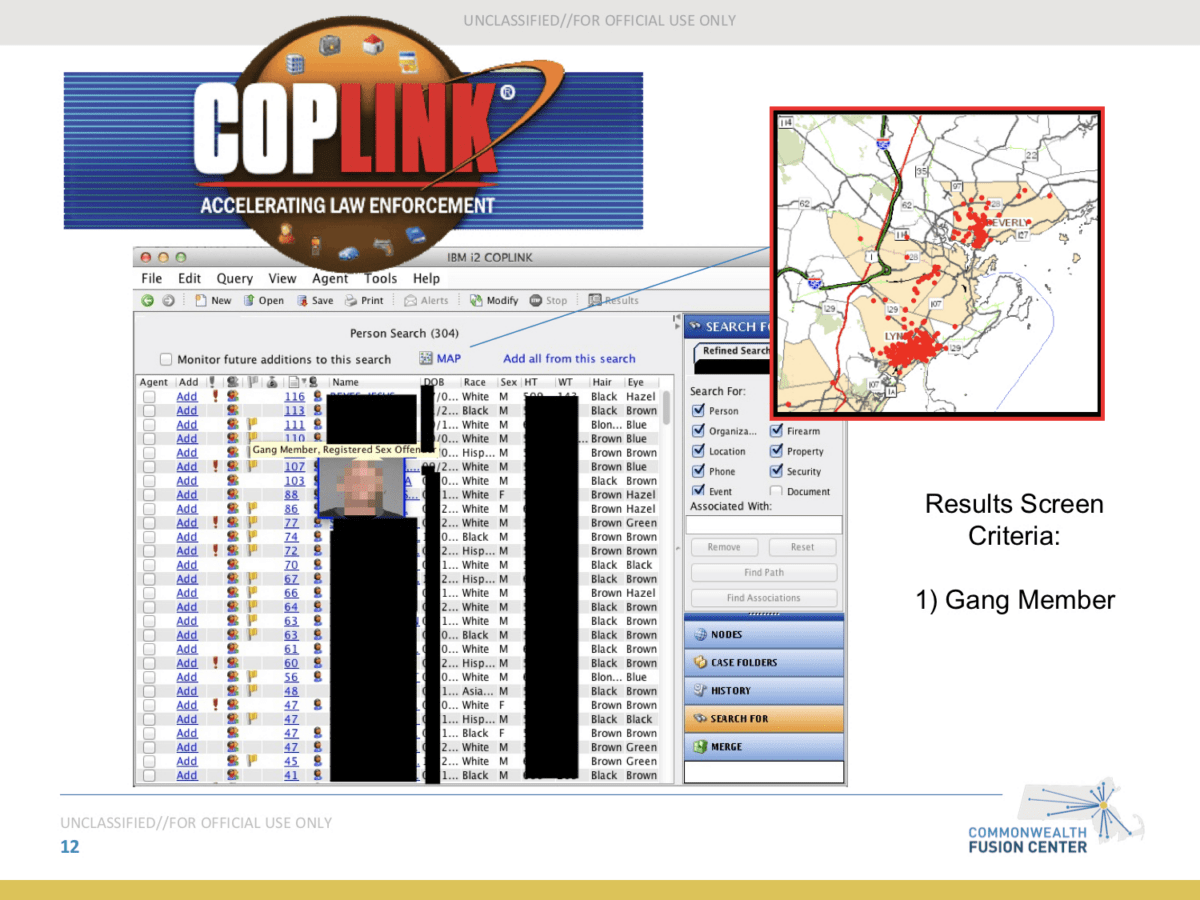

In the slide below, the state police attempted to redact information, concealing their investigative techniques with black boxes. The black boxes on the files, however, can be deleted. The Massachusetts State Police did not respond to The Appeal’s inquiry about the original redactions. The Appeal has chosen to publish select portions of the redacted documents, with some new redactions added to protect people’s identities, to show the tremendous search capabilities the program affords users, whether they be local cops or ICE agents. This document, for example, shows that police officers and ICE agents using COPLINK can also filter through masses of records to find people alleged to be gang members.

Work that would have taken months in the past, and required piecing together disparate data points from agencies across the state, can now be done with a few clicks, says Lieutenant Michael Kmiec of the Lynn Police Department in Massachusetts. “It speeds up the process in looking at information in other departments. Instead of calling the other department, you can pull it directly,” said Lieutenant Kmiec to this reporter, then a freelancer with ProPublica, in a phone call last September. “Regarding the FBI and ICE, if they’re looking to look up a name or vehicle information, it’s a database accessible to them to look up things quickly.”

Clashing Interests: Law Enforcement vs. Immigrants’ Rights

Law enforcement officials interviewed by The Appeal argue the sharing of residents’ data with ICE has clear benefits at both local and federal levels.

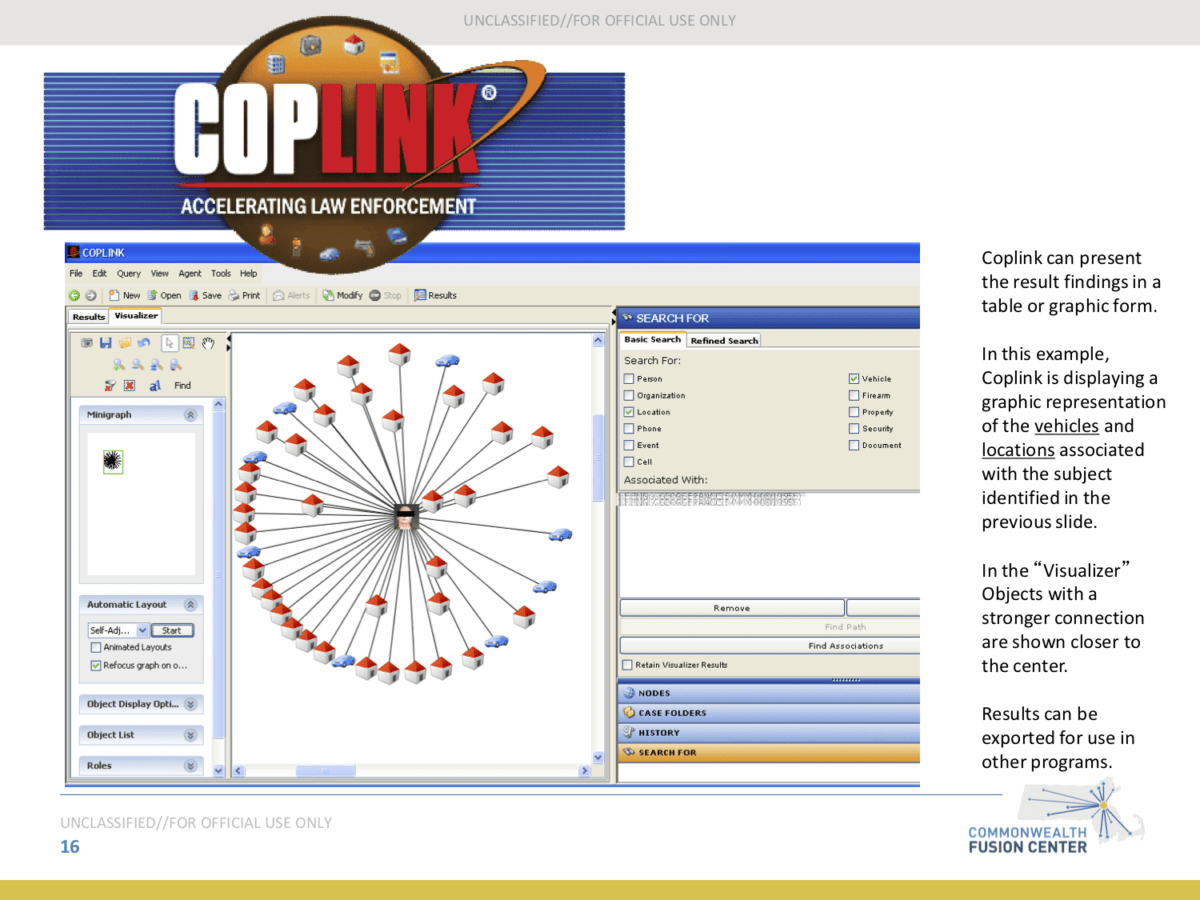

Local databases and analytic tools, like Massachusetts’s COPLINK system, are a treasure trove for ICE HSI special agents because they provide granular data that federal agents often lack, says John Sandweg, former acting director of ICE in 2013 and 2014. “Say you have a suspect and you’re working on a federal case, you want to tap into the information, do associate mapping, link analysis — it can be huge for an investigation,” said Sandweg in a phone call. “They’re going to have more information than the feds.”

For ICE’s worksite enforcement operations, analysts rely on this type of local police data to do deeper background checks on undocumented employees. Claude Arnold, a retired ICE special agent who led the agency’s national gang initiative, Operation Community Shield, explained how it works. “Say they’re preparing a worksite case and they’re running all the employees of the company. They’re going to run criminal checks, but the NCIC [National Crime Information Center] and other federal databases wouldn’t have field interview cards [in which police transcribe notes on interactions with or observations of civilians],” he told The Appeal. While NCIC contains some gang information, COPLINK would be more likely to have information on employers, associates, and hangout spots, he explained. “It would sweeten the pot if a bunch of the employees are criminal aliens. When you go to the U.S. Attorney’s Office, you can say not only are they employed illegally, there are two gang bangers and this guy has two illegal entries.”

The help goes both ways. Local law enforcement sometimes calls on ICE HSI to deport alleged gang members when local authorities don’t have enough evidence to lead successful investigations themselves, Sandweg points out. “Say you got a guy who’s been deported and he’s back, it may be difficult to find probable cause on him for a criminal investigation, but it’s easy to do civil proceedings for a deportation,” said Sandweg. “Maybe some innocent people have been picked up, but HSI has got a lot of violent felons off the streets.”

Arnold reiterated this point, noting that local police routinely rely on this kind of collaboration with ICE. “Typically, what would happen is the local police would give me a list of the people in that gang, and then we just do a full workup on all of them, and that’s what you’d use COPLINK for,” said Arnold, referring to research done on the targets’ immigration status and their potential criminal and civil immigration violations.

Lieutenant Quinn of the Massachusetts State Police says that people should not be concerned about these search capabilities being shared with ICE Homeland Security Investigations because much of HSI’s work focuses on high-level cases.

“We work with HSI on the criminal side. They do a lot of criminal work and that’s what we help with,” said Quinn to this reporter, then a freelancer with ProPublica. “It’s just plain old criminal work that has been enhanced by these tools,” he added, referring to the fact that ICE HSI carries out a wide range of investigations, from financial and cyber crimes to export enforcement and weapons smuggling.

But those aren’t the only types of investigations handled by ICE HSI, explains Maddie Thomson, an immigration attorney at Boston’s Community Law Office. The example she cites isn’t about a COPLINK case, but does show the breadth of the agents’ work and their reliance on local police records.

In March, one of Thomson’s clients, a young Salvadoran man who was classified as a gang member despite having no criminal record, was deported after having entered the country without inspection, a civil matter, following an ICE HSI investigation.

The evidence cited in immigration court for his alleged membership in MS-13 were all local police documents, school police observations and field interrogation and observation (FIO) records, which ICE in this case pulled from a Boston police gang database. In smaller jurisdictions that do not feed records into a gang database, however, ICE could have just as easily used COPLINK to pull the same records.

In immigration court, Thomson’s client’s familiarity with other alleged gang members helped greenlight his deportation. “The DHS attorney would ask him, ‘Do you know this person? Do you know that person is a gang member?’ and he’d say, ‘No, I just knew him as someone playing pick up soccer in the park,’” recalled Thomson. In February 2018, her client received a final removal order. He was put on a plane to El Salvador last month.

ICE’s willingness to remove undocumented people who could not be prosecuted through domestic criminal courts violates the spirit of due process, argues Sarah Sherman Stokes, a clinical instructor in the Immigrants’ Rights Clinic at Boston University School of Law.

“For them, it’s better if a bunch of innocent people get apprehended than letting one guilty person go free,” said Stokes, who has represented young immigrants put into deportation proceedings due to ICE HSI investigations. “I’m incredibly troubled by the kind of information-sharing happening with local law enforcement and ICE, and am increasingly disturbed by the role of HSI in apprehending immigrants, whom there otherwise wouldn’t be probable cause for law enforcement to apprehend.” ICE declined to comment on HSI’s role in immigration proceedings.

Where and How Local Police Data Is Being Shared

Several of the 25 police departments sharing data with COPLINK are in the greater Boston area, home to many of the state’s largest and densest undocumented communities, even so-called “sanctuary” cities, such as Bostonand Cambridge.

In the interactive map below, viewers can see where local police departments are fully sharing or in the process of sharing data with COPLINK, and, in effect, with ICE. Click on the department dots to see their data-sharing policies and on the census tracts to see the density of foreign-born, non-citizen residents, as estimated by a 2016 U.S. census dataset:

How an individual is defined as a gang member varies based on local policing practices, but, as advocates point out, these important distinctions are blurred in an aggregated data system and can net the wrong people into COPLINK.

The software ingests police data from local records management databases, but the definition of gang membership, for example, varies across the state, says Captain Harry Hess, a technical services commander at the Fitchburg Police Department. In Fitchburg, Hess said in a phone interview with The Appeal, officers base gang classification on a case-by-case assessment of things like tattoos, interviews with the individual in question, or their known associates.

In Boston, on the other hand, police use a more defined points-based formula, as Crockford recently explained in a piece for The Appeal. This points-classification system is based on adding up questionable “gang” indicators, such as who an individual has been seen speaking to, their clothing colors, and police judgements about their photos on Facebook.

But that means COPLINK users, whether they are cops from neighboring counties or federal immigration agents, have no way of knowing what local police practices culminated in an individual getting labeled as a gang member.

“If you’re looking for a suspect in a car break-in and you knew he was a Latin King in a certain age range, you want to have those labels to search for a suspect that might match,” said Kristi Fritscher, a crime analyst at the Fitchburg Police Department in a phone interview with The Appeal. “But how they came to that conclusion is not in there.”

The varying data-collection practices used by departments feeding into COPLINK could raise a “junk in, junk out” problem for immigrants or anyone added into the system, Crockford argues.

“If someone from ICE HSI searched for gang members in Massachusetts, that person doesn’t necessarily know if someone has been identified as a gang member by a Somerville police official just because they had a hunch or by a Waltham officer because they killed three people,” said Crockford. “There’s a flattening that takes place, where allegations by local police who may have no idea what they’re talking about, suddenly looks the same as allegations of real violence.”

Sanctuary Cities Respond

Regardless of the quality of the information, immigration advocates say, it’s dangerous for cities to share it with ICE and disappointing that sanctuary cities would do so.

“The fact that police are sharing information [with ICE] clearly violates the spirit of the sanctuary idea,” said Thomson, referring to COPLINK. “So it’s very easy for cities to get liberal cred, while also participating in these systems and actively helping to deport people.”

Jonathan Fu, a spokesperson for the city of San Gabriel, California, responded to a request for comment from The Appeal on why his sanctuary city uses COPLINK. “The San Gabriel Police Department has access to COPLINK, which allows us to search for data related to criminal reports. The system does not allow us to list immigration status, nor do we provide such information to COPLINK.” Fu added that the city wants undocumented immigrants to be able to come forward with relevant information about crimes to law enforcement without fear of deportation, but he did not bring up any plans to alter the department’s data-sharing practices.

Denise Taylor, a spokesperson for the city of Somerville, Massachusetts, responded to a similar request from The Appeal. “The safety of all of our residents and the protection of our families regardless of status remains a top priority for the city and undergirds our sanctuary city/safe city policies,” she wrote in an email. “[We] will certainly carefully review this with local law enforcement and other sanctuary cities to determine the best policy going forward.”

The mayors’ offices of the two other Massachusetts’s sanctuary cities that feed into COPLINK — Boston and Cambridge — declined to comment on their cities’ use of the program. Mayors’ offices in two other California sanctuary cities that contribute to a Los Angeles County-wide COPLINK database, Los Angeles and Pasadena, did not comment on the matter.

Other elected officials in those cities interviewed by The Appeal expressed varying degrees of discomfort with this data-sharing.

Lydia Edwards, a Boston city council member and attorney from the heavily immigrant community of East Boston, noted that currently, Boston’s sanctuary policy only shields undocumented immigrants from ICE’s civil detainer requests to hold arrestees in jail for pick-up by ICE agents, not from information-sharing more broadly.

In a statement, Edwards noted that while this detainer component is beneficial, it’s not enough. “As a city, we should be transparent about the data we collect, who we are sharing it with, and what public purpose it serves so that these agreements can be fully vetted,” Edwards said.

Likewise, J.T. Scott, an alderman from Somerville, said in a statement that the Somerville police department’s participation in COPLINK “certainly raises troubling questions about how much information ICE HSI can obtain about residents of our city,” and added that he will be raising the issue through the city’s Board of Aldermen.

On the other hand, Quinton Zondervan, a Cambridge city council member, argued that data-sharing with ICE HSI is necessary for serious criminal investigations, even if it means ICE can use the information for immigration-related purposes. “It’s very hard to prevent that,” said Zondervan in a phone call with The Appeal.

While some local officials are calling for greater transparency regarding their data-sharing with ICE, none have definitively called for their police departments to stop using COPLINK or limit ICE’s access to their residents’ data through, for example, amendments to the agencies’ data-sharing agreements. While legal experts differ on whether or not cities could prevent ICE from accessing local police data altogether, Crockford says amending such agreements would weaken ICE’s ability to mine millions of records at once and instantly piece together people’s connections.

Localities seeking to protect immigrant communities should “conduct comprehensive reviews of their information sharing systems,” said Crockford. “That’s just as important as refusing to honor detainer requests, but because all of these police data systems were built and maintained out of the public view, it hasn’t gotten the same attention.”

Thomson said it’s hard to get lawmakers to take action on this data-sharing issue given undocumented immigrants’ current lack of political power.

“Generally, this is a population whose experiences are not shared by voters,” said Thomson, since most voters do not have families of mixed legal status. “So it is really easy for elected officials to not really address what’s happening.”