How the Push to Close Rikers Went From No Jails To New Jails

Activists say a once-radical campaign has been co-opted.

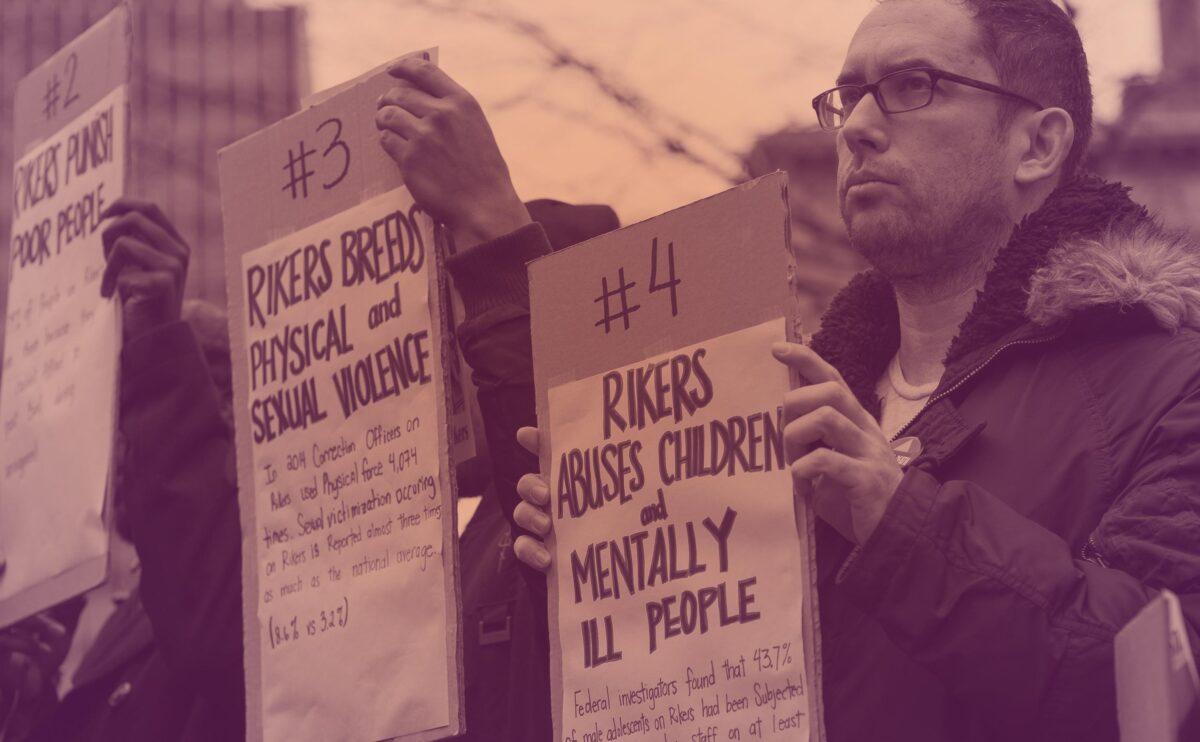

On Nov. 10, 2015, Joseph Ponte, then New York City’s Department of Correction (DOC) commissioner, addressed a packed hearing of the Board of Correction to discuss violence on Rikers Island. Soon after Ponte began speaking, three people walked toward the front of the room, unfurled a banner for the Campaign to Shut Down Rikers, and chanted “Hell no to the status quo! These prison walls have got to go!” They kept chanting, even getting louder, as they were kicked out of the meeting. Before they were escorted out, though, two more people in the crowd stood up, and raised a sign bearing the face of Kalief Browder, a Bronx teen who spent three years on Rikers, much of it in solitary confinement, for allegedly stealing a backpack. Browder took his own life soon after his release, a tragedy that helped catalyze the movement to close the jail. The protesters began shouting reasons Rikers Island needed to be shut down: “Rikers is racist!” “Rikers is a torture chamber!”

The activists were part of a group called the Campaign to Shut Down Rikers, a coalition including Akeem Browder, Kalief’s brother; advocates from Millions March NYC, a grassroots collective; and members of Jails Action Coalition, an alliance of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people and their supporters. The campaign’s mission was to get the notorious Rikers Island jail complex shut down for good. But in addition to closing Rikers, the coalition also had a more radical demand: that the city divest entirely from police and prisons and invest in communities. The campaign demanded that the money being put into incarcerating and policing people be used for education, healthcare, housing, and other basic needs.

Organizers had long targeted Rikers Island for reform. Groups like Resist Rikers had been holding rallies at the jail complex since 2014, calling attention to its use of solitary confinement and the infamous brutality of its guards. Jails Action Coalition had been organizing against the DOC’s solitary confinement practices for the previous two years, and its members were some of the first people to publicly call for Rikers’ closure. For the next year, the Campaign to Shut Down Rikers would organize vigils, marches and rallies, including one in which they dropped off a coffin at City Hall bearing Browder’s name.

But as the movement gained momentum, it also lost its focus. At the beginning, calls to shut down Rikers Island came from grassroots activists with an abolitionist agenda. Prison abolitionists aim to make police and prisons obsolete by addressing the root causes of social ills. By 2017, when Mayor Bill de Blasio announced the city’s “Roadmap to Closing Rikers Island” within 10 years and open four new neighborhood jails, advocates say, the plan to close Rikers had been defanged and distorted.

“The topic of shutting down Rikers has breached and found some permanence in mainstream conversation,” the #ShutDownRikers group wrote in a public statement in 2016. But that wasn’t necessarily a good thing. “A variety of liberal political figures began weighing in, rapidly co-opting the work of the grassroots movement that valued, above all else, community inclusion,” the statement continued. “The conversation [about] closing Rikers has become increasingly synonymous with building new neighborhood jails, which is entirely incompatible with our campaign’s abolitionist perspectives.”

Same goal, different paths

Calls to shut down Rikers started to grow louder in the fall of 2015. City Council member Daniel Dromm began to speak out in favor of closing Rikers, and it became a frequent recommendation from advocates at Board of Correction meetings.

On Nov. 18, 2015, Glenn Martin, then president of JustLeadershipUSA (JLUSA), a group focused on ending mass incarceration, spoke at a conference about whether to reform or shut down Rikers Island. Participants included City Comptroller Scott Stringer, who agreed that Rikers should be closed. It was a precursor to JLUSA’s not-yet-public campaign, #CLOSErikers, which quickly took off. The nonprofit received grants in late 2015 and 2016 from the Open Philanthropy Project, which also helps fund The Appeal, to support its campaign, as well as multiple grants from the Ford Foundation since at least 2014. With this support, JLUSA led a coalition of 50 other organizations and publicly launched its #CLOSErikers campaign on April 14, 2016, with a rally at City Hall.

But the goals of the earliest advocates fell by the wayside. “Unlike us, [JustLeadership] never took a clear stance from the beginning on building more neighborhood jails,” said Nabil Hassein, an organizer who worked on the Shut Down Rikers campaign. “We were always very clear and explicit about [opposing new jails] from the beginning and we didn’t see that from them. And when you have these well-funded nonprofit groups coming in, in a lot of ways, they had more capacity to do things than we did.”

When then-Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito made her State of the City address on Feb. 11, 2016, Kalief Browder’s mother was in the audience. Mark-Viverito dedicated a section of the speech to Kalief, saying, “Kalief entered [Rikers] as a child, but left as a broken man. A few months later, Kalief died by his own hands. It was not one failure which led to his death; it was generations of failures compounded on one another.”

Mark-Viverito announced that she would be forming a commission led by former New York State Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman (later dubbed the Lippman Commission) to identify ways to reduce the population on Rikers Island so that closing the jail complex could become a reality. It consisted of 27 commissioners, including Martin, along with representatives from nonprofits like the Vera Institute for Justice and the Legal Aid Society. The commission also included multiple judges from New York City courts, a former U.S. attorney, the president of the Ford Foundation, and the president of the Citizens Crime Commission.

Meanwhile, the #CLOSErikers campaign had grown into a coalition with more than 170 partner organizations, including some of the city’s biggest nonprofits. JLUSA’s support from foundations also grew, with grants from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative and Google’s charitable arm, Google.org. Over the next year and a half, the campaign organized rallies outside de Blasio’s fundraisers when he was up for re-election. Its members confronted the mayor at his Brooklyn gym and attempted to confront him at his polling station to persuade him to shut down the jail complex. They also put up billboards in Harlem and Times Square urging de Blasio to close Rikers.

Martin saw closing Rikers as a moral imperative that would involve multiple reforms to New York City’s criminal justice system, like reducing the use of cash bail. He called for increased social services and public investment in healthcare, education and jobs, but saw at least some of those services being delivered through community-based jails. “There is no question that access to job training, healthcare, drug and alcohol and mental health treatment are among the important services that will be easier to provide in community facilities rather than at Rikers Island,” Martin said in a 2016 interview with Grist.

But organizers with the Campaign to Shut Down Rikers say Martin, who had become the leader of #CLOSErikers, was too quick to agree to replacing Rikers with other jails.

“All the problems with Rikers are symptoms of the larger problem of incarceration,” Hassein told The Appeal. “The only reason to build new jails is because the city is actively planning to incarcerate more people rather than actually addressing the issues that lead to incarceration.”

“I’m not saying that people in jail shouldn’t have access to services, but you’re putting human beings in a cage,” he added. “What kind of mental health effects do you expect? If you want to improve their mental health, why are you keeping them in a cage?”

Five Mualimm-ak, a Jails Action Coalition member, echoed those concerns. He told The Appeal that by investing in new jails, the city will end up simply “shipping old problems and old brutal cultures to a new address.”

For JLUSA, a gradual approach seemed more pragmatic. “Glenn and campaign leaders directly impacted by Rikers felt an urgency to get people off of Rikers as a human rights imperative being that the culture of violence and toxic air conditions they experienced are intolerable,” Brandon Holmes, the #CLOSErikers campaign coordinator at JLUSA, told The Appeal. “On the way to creating the conditions and support for complete decarceration of New York, we must demand the least restrictive conditions, and keeping anyone who is detained close to their homes, their families, and their community-based support services.”

In December 2017, Martin resigned from JLUSA after being accused of sexual misconduct. He declined to comment for this story.

But organizers’ critiques of the #CLOSErikers campaign extend beyond Martin or JLUSA’s decision to support community jails; they question the group’s ability to decouple itself from its funders’ interests. “The police and the prisons, at the end of the day, exist to preserve the existing social order, which is one that benefits rich people and harms the people being incarcerated,” Hassein said. “I think there’s an inherent tension in trying to have an organization be against incarceration while also being accountable to wealthy donors as opposed to being accountable to the communities that they’re working in.”

The 27 Lippman commissioners met for over a year—going on jail visits, analyzing data and hosting town halls. When their report came out in April 2017, their recommendation on what should be done with Rikers was clear.

“We have concluded that simply reducing the inmate population, renovating the existing facilities, or increasing resources will not solve the deep, underlying issues on Rikers Island. We are recommending, without hesitation or equivocation, permanently ending the use of Rikers Island as a jail facility in any form or function,” the report said. “The Island is a powerful symbol of a discredited approach to criminal justice—a penal colony that subjects all within its walls to inhumane conditions.”

The report was split into three categories: reducing the jail population in New York by “creating off-ramps” before arrests occur and shortening pretrial detention; building more humane jails; and reimagining Rikers Island as a place for development.

In order for Rikers Island to close, however, the jail population would have to decrease significantly. The Lippman Commission’s suggestions for reducing the jail population included eliminating bail in favor of pretrial supervision, which can mean house arrest, curfews, electronic monitoring, or required drug treatment. “It should become the default option, replacing money bail, for those who are charged with misdemeanors and nonviolent felonies, as well as for some young people charged with more serious offenses,” the report states. (Most people charged with misdemeanors now get released on their own recognizance, depending on the outcome of their risk assessments.)

But even with fewer people detained pretrial, its authors asserted, the city would still need new and renovated neighborhood jails to close Rikers. “The Commission believes that confinement is necessary when individuals are a threat to others, but that its use should be a last resort,” the report stated.

To reduce the jail population, the commission also recommended that the city use risk-assessment tools to determine a defendant’s risk of re-offending, risk of future violence, and risk of future domestic violence. Currently, the criminal court system uses a tool that assesses whether a defendant will show up to court dates. Other recommendations included elimination of all sentences with a jail time of 30 days or less.

Hassein and other advocates from the Shut Down Rikers campaign saw the recommendations as insufficient. “The movement to abolish bail is important and is a step towards abolition,” Hassein said, “but I feel like the expansion of pretrial supervision is just more surveillance and repression of communities.”

The mayor’s plan

By this point, Mayor de Blasio, who had described closing Rikers as a “noble concept” but virtually impossible to achieve, was having City Hall staff research possible jails to replace the complex. For the past four years, de Blasio has been trying to implement reforms on Rikers to address its “culture of violence.” The reforms, some of which were described by advocates as punitive to the people housed there, were generally considered a failure. Just two days before the Lippman report was released publicly, in what observers considered a capitulation to public pressure and an attempt to save face, he came out in favor of closing Rikers but said the process would take 10 years, a timeline that dismayed many activists.

“Ten more years means at least $10 billion of taxpayers’ money wasted on a failed jail system. Ten more years means over 400,000 New Yorkers going to Rikers. He won’t even be in office in 10 years so the 10-year timeline doesn’t make sense,” Darren Mack, an organizer with JLUSA, told The Appeal.

Three months later, on June 22, 2017, Mayor de Blasio officially released his plan to close Rikers, but it wasn’t until February 2018, that the mayor announced that he had reached an agreement with the City Council to build new “community-based facilities.”

De Blasio’s plan to close Rikers consists of a neighborhood jail in every borough except Staten Island. In Brooklyn and Manhattan, this would mean significant renovations on two currently operating jails. In the Bronx, the city would build a new facility and in Queens, the city would reopen and renovate the Queens Detention Center. The Vernon C. Bain Correctional Center, a jail in the Bronx known as “The Barge” would remain open. The result would be five DOC jails with a total capacity of 5,000 people. Council members responsible for the various jail locations reached an agreement with the mayor to conduct a single public review process for all four sites to expedite building the new jail facilities.

Even if it is sped up slightly, however, many organizers are not impressed with de Blasio’s plan. For the people who first called to shut down the island, the idea of “neighborhood” jails sounds absurd.

“There is no such thing as community jails,” Mualimm-ak of Jails Action Coalition told The Appeal. “We live in a city with well over 60,000 homeless people and thousands more living in someone else’s home. There are more vital needs that aren’t being addressed in New York City than investing in properties that will hold people instead of helping people.”

Mack said Mayor de Blasio did not consult with campaign members or the people most directly impacted before releasing his plan. “The #CLOSErikers campaign [doesn’t] support the mayor’s proposal,” he told The Appeal. “We believe in human rights and dignity and that no one should be on Rikers, which is completely inhumane and irredeemable. It’s the Abu Ghraib of New York City. … We don’t want Rikers or the culture of violence to be moved from that toxic wasteland into our communities. We don’t need 21st-century jails. We need 21st-century communities.”

Patrick Gallahue, a spokesman from the mayor’s office, noted that its Implementation Task Force includes nonprofit advocates—some of whom were formerly incarcerated—service providers, and government officials like the city’s five district attorneys and the New York Police Department commissioner. “Before and after the Roadmap’s publication, the City has met with and worked closely with a broad group of leaders,” Gallahue wrote in an email. “This has been carried out both in private meetings as well as public events. We are by no means finished. … That will continue and expand very soon. While the work is firing on all cylinders, we welcome input and there remain many opportunities to be involved.”

In order for de Blasio’s plan to work, the jail population, currently at about 9,000 would have to shrink by around 44 percent, according to the mayor’s office. (Former Correction Commissioner Martin Horn says the city could squeeze in 3,000 more beds, if necessary, under current zoning laws.) This is where the city’s other planned reforms come in. In the Roadmap to Closing Rikers Island, the mayor’s office outlines a number of changes aimed at achieving a 50 percent reduction in the jail population in ten years. The reforms include: making it easy to pay bail, replacing short jail sentences (30 days or less) with programs that reduce reoffending, improving the city’s assessment tool to determine flight risk, reducing case delay, and speeding up the transfer of people who violate their parole to state prisons (thereby reducing their time spent in New York City jails).

The Roadmap also envisions building more humane jails by expanding mental health units in DOC jails, for instance, allocating $100 million to a new correction officer training academy, and bringing all facilities including the eight jails on Rikers Island to a state of good repair as an interim measure before the complex is closed.

But these reforms mainly focus on speeding up the process of putting someone through the system and then improving their experience—not stopping people from getting in contact with the system in the first place.

That doesn’t sit well with the first generation of activists who tried to close down Rikers, or the second generation. While JLUSA stands by the Lippman Commission’s report calling for neighborhood jails, Mack said the report was a compromise that did not include all of JLUSA’s demands. As for Mayor de Blasio’s plan to close Rikers: “Our campaign is committed to justice and systemic change, not just reform. The mayor’s Roadmap lacks serious investment into communities that have been historically under-resourced,” he told The Appeal. “It falls short on ending the mass criminalization of communities of color and poor people in this city.”

A ‘vicious cycle’

All the activist groups contacted by The Appeal expressed disappointment in de Blasio’s plan. Many noted one glaring omission: There was no mention of ending broken windows policing, or other aggressive NYPD policing practices, in the plan to reduce the number of people incarcerated in New York City.

Critical Resistance New York City, a prison-abolitionist group, has demanded that Rikers be shut down and not replaced with new jails and that the NYPD end policies like broken windows policing and community policing which, the group wrote, “only increase police presence in our neighborhoods and broaden their jurisdiction over virtually every aspect of our lives, especially in communities of color.”

Although de Blasio and the city’s police have said they stopped arresting people for possession of small amounts of marijuana, for example, they continue to do so. The NYPD also continues to arrest a large number of people for “fare-beating,” going so far as to pressure Manhattan District Attorney Cy Vance’s office to continue prosecuting fare-beating arrests after the DA announced reforms.

“When you just look at the scale of resources that the city is investing in incarcerating our communities versus the scale of resources that go to things like education, to jobs, to health care including mental health care—or you know, the damn subway,” Hassein of Shut Down Rikers said. “Instead of locking people up and sending them to Rikers Island over $2.75 subway fare, maybe that money could be going to free subway fare.”

In 2017, JLUSA launched the #FREEnewyork campaign to demand statewide bail reform, speedy trial reform, and discovery law reform. “#CLOSErikers is in the process of gathering community input through forums in majorly impacted neighborhoods and we are prioritizing a mapping of needed community resources. We are pushing for decarceration in all ways,” Holmes said. “We are calling for an end to broken windows policing, ensuring diversion before arrest, etc. Building communities includes repairing the harm caused by Rikers Island.”

Despite all that has occurred in the fight to close Rikers, grassroots activists have held tight to the abolitionist goals of the movement. Community groups have voiced their opposition to new jails being built in their communities while also demanding that Rikers Island be closed.

Although the Campaign to Shut Down Rikers officially disbanded in June 2016 after releasing a statement, members of the coalition have continued to organize with other groups. The group now plans to strategize “effective next steps in confronting agendas that promote re-incarceration, such as smaller community jails and other rebranded extensions of the racist police state,” Shut Down Rikers wrote in its statement. “We continue to demand that the City of New York divest from jails and instead, invest funds into communities that are sorely lacking adequate educational, health and mental health, and employment resources and services—all of which would serve to ultimately decarcerate NYC.”

Critical Resistance, South Bronx Unite and the Diego Beekman Mutual Housing Association of Mott Haven have all published public statements opposing the proposed jails, while calling for Rikers to still be shut down.

“The problem is not the facilities; this is a vicious cycle and there’s no way to reform a system that isn’t meant to work,” said Reuben, a Critical Resistance comrade incarcerated in New York, who provided only his first name. “Rikers is only a holding place for victims of an unjust system. Closing down a jail is not really addressing our real problem.”