Before Children’s Grisly Deaths, a Family Fought for Them and Lost

The Hart family’s apparent murder-suicide drew headlines, but the path to the tragedy started much earlier—in Texas.

Two neighbor kids bang on Sherry Davis’s door. They’ve seen her come home and know she can be counted on for handing out the little packs of Starburst she keeps nearby. Outside, the dingy affordable-housing complex in South Houston is overflowing with neighbors—a baby toddles after a young puppy, several guys hang around their cars.

Davis, visibly distraught, gives out some candy, but after she closes the door, her grief overcomes her. She hugs her best friend in the kitchen of her dimly lit apartment, and together they wail. Clarence Celestine, the father of two of Davis’s kids, shifts his body on the couch nearby, rubs his hands together, and tries to stay composed.

It’s April 13, and it’s been two days since they heard the news of what happened to her children. Two weeks earlier, 2,000 miles away in Mendocino County, California, a gold Yukon SUV was found at the bottom of a 100-foot cliff. Devonte, Jeremiah, and Ciara, along with their three adoptive siblings, were believed to have been inside. The bodies of the children’s adoptive mothers, Jennifer and Sarah Hart, were found in the driver’s and passenger’s seats; police suspect the plunge was intentional. After the crash was discovered, abuse allegations that had followed the family through three states and over 10 years began trickling out, forming a harrowing account of what had happened to Davis’s children since she had last seen them 12 years ago.

But for Davis, the grief was still shrouded in shock—she’d found out about the crash more than two weeks after it happened, when Celestine’s sister Priscilla Celestine was alerted by her former lawyer and called Davis with the news. “If she hadn’t found out, I don’t even think they would have told me,” Davis said in April. “They haven’t told me yet; they haven’t called or nothing.”

Davis lost custody of her children because of her cocaine addiction; she and Celestine gave up their parental rights in 2006. They hoped the children would be adopted by Priscilla, who had a stable job and no criminal record and who took in all four of Davis’s children. But Priscilla’s plans to adopt were dashed after a caseworker discovered Davis babysitting the children while Priscilla was at work.

As Priscilla continued to fight for the children, they were adopted in 2009 by the Harts, a couple based in Minnesota, who had already adopted three other children, Markis, Hannah, and Abigail. Although a string of abuse reports and investigations across several states would follow, the Harts’ carefully crafted narrative of a passel of formerly abused black children and two progressive white moms fighting for them gave them a cover for their own abuse.

The Hart children’s story exposed myriad flaws in the country’s child welfare system, where spotty communication between agencies in different jurisdictions let the Harts slip through the cracks as they fled from state to state, becoming increasingly isolated from the outside world. But it also shows the power of the Texas court that took the children in the first place. Rather than working to keep the children with their families, the court had a reputation for speeding up adoptions, and leaving frustrated and despairing family members in their wake.

An idyllic facade

For a long time, through the prism of social media, it looked as though the Hart children were leading a charmed life. Jennifer Hart regularly shared idyllic snapshots of the siblings playing with chickens, attending music festivals, roadtripping to national parks, reading books in the woods. They posted photos on Facebook of their adventures: two white lesbian moms, clutching their six black children, often in matching outfits, with wide grins plastered across all of their faces.

Hart and her wife, Sarah, made it seem as if they had rescued their children from horrible abuse. In a 2014 article on a New Zealand-based website called Paper Trail, Jennifer Hart said her son Devonte was born with “drugs pumping through his tiny body.” At 4 years old, Hart told the website, “he had smoked, consumed alcohol, handled guns, been shot at, and suffered severe abuse and neglect.” He had known few words besides curse words, was violent, and had disabilities, she said.

When the Hart family moved to a suburb of Portland, Oregon, in 2013, Devonte became a notable local fixture for the “Free Hugs” sign he would tote along to protests and festivals. In 2014, a photo of Devonte tearfully hugging a cop at Portland’s Black Lives Matter protest went viral. “People always tell us how lucky he is that we adopted him,” Hart told the New Zealand website two weeks before Devonte’s viral photo was taken. “I tell you, we most certainly are the lucky ones. Yes indeed, he is living proof that our past does not dictate our future.”

Still, there were early signs that the life the kids were leading was far from picture-perfect. In 2008, when the Harts were living in Alexandria, Minnesota, a teacher noticed a large bruise on Hannah, then 6, and reported it. Hannah told authorities that her mother had hit her with a belt; the Harts said the child had fallen down the stairs, and no charges were filed. Several months later, in February 2009, Devonte and his siblings were formally adopted into the family. In 2010, teachers saw bruises on 6-year-old Abigail. Although she told authorities that Jennifer Hart had hit her, Sarah pleaded guilty to misdemeanor domestic assault. She admitted at the time that she “let her anger get out of control” in disciplining the child, according a police report. But the children remained with the two women, who removed them from public school after the incident.

Later, after the family had relocated to Oregon, friends of Jennifer and Sarah noticed they were extremely restrictive with the children’s food; one reported the couple to authorities there. Portland child welfare workers opened an investigation and found the children were so small that five of them weren’t even on growth charts for their age groups, according to public records obtained by the Oregonian. In Washington, neighbors grew concerned when Devonte showed up begging for food “a dozen times.”

Each time a concerned person reached out or investigated, Jennifer and her wife had an explanation: It was the kids’ traumatic childhoods before they were adopted that led to their strange behavior and eating habits, the Harts insisted. A Minnesota child welfare worker explained the phenomenon in documents released by the Oregon Department of Human Services: “The problem is, ‘these women look normal’ and the[y] give professionals the information about all the children being adopted because they are high needs, and have mental health issues related to food, then people tend to assign the problems to the children,” she said. After each investigation, the Harts were allowed to keep the kids.

But abuse allegations followed the Harts to their two-acre property in Woodland, Washington, where Child Protective Services (CPS) did a welfare check in late March this year, and arrived to an empty house. Their SUV would be discovered on March 26, along with Jennifer and Sarah Hart and three of their children, all dead. Ciara (who was renamed Sierra by the Harts) would later be found in the ocean and identified. Devonte and Hannah remain missing.

Members of Devonte, Jeremiah, and Ciara’s family say none of this should have happened, and not just because of the abuse the children apparently suffered at the hands of their adoptive parents. They describe an earlier tragedy inflicted by a juvenile court in Harris County, Texas.

A forgotten family

The picture of Devonte, Jeremiah, and Ciara’s early childhood that the Harts painted so clearly—Devonte smoking and being shot at, for instance—doesn’t square with their family’s memories of the children. “Please. I heard all about that, just lying. That stuff they just made up,” Davis said.

She has her own memories. “Devonte was real smart—always quiet, observing, watching,” Davis recalled. While the oldest, Dontay, would rough-house with Jeremiah, Devonte (or Baby D as his mother called him) would sit quietly and watch “Dora the Explorer,” his favorite show.

But Davis battled with drug use. Court documents call her “a long-time crack-cocaine abuser,” and she lost two families over the course of her life. Her first three children were removed from her care in the 1980s and her parental rights were terminated. Court documents note that one of her older children had multiple bone fractures when he was removed from her care.

She then lost custody of her youngest children upon Jeremiah’s birth in 2004, when she was found to have cocaine in her system. Devonte, Jeremiah, and their older brother Dontay went to live with Nathaniel Davis, their mother’s longtime boyfriend, although he’s not biologically related to any of the children. When Ciara (whose name is spelled Ciera in court documents) was born in 2005, she briefly joined them in his care.

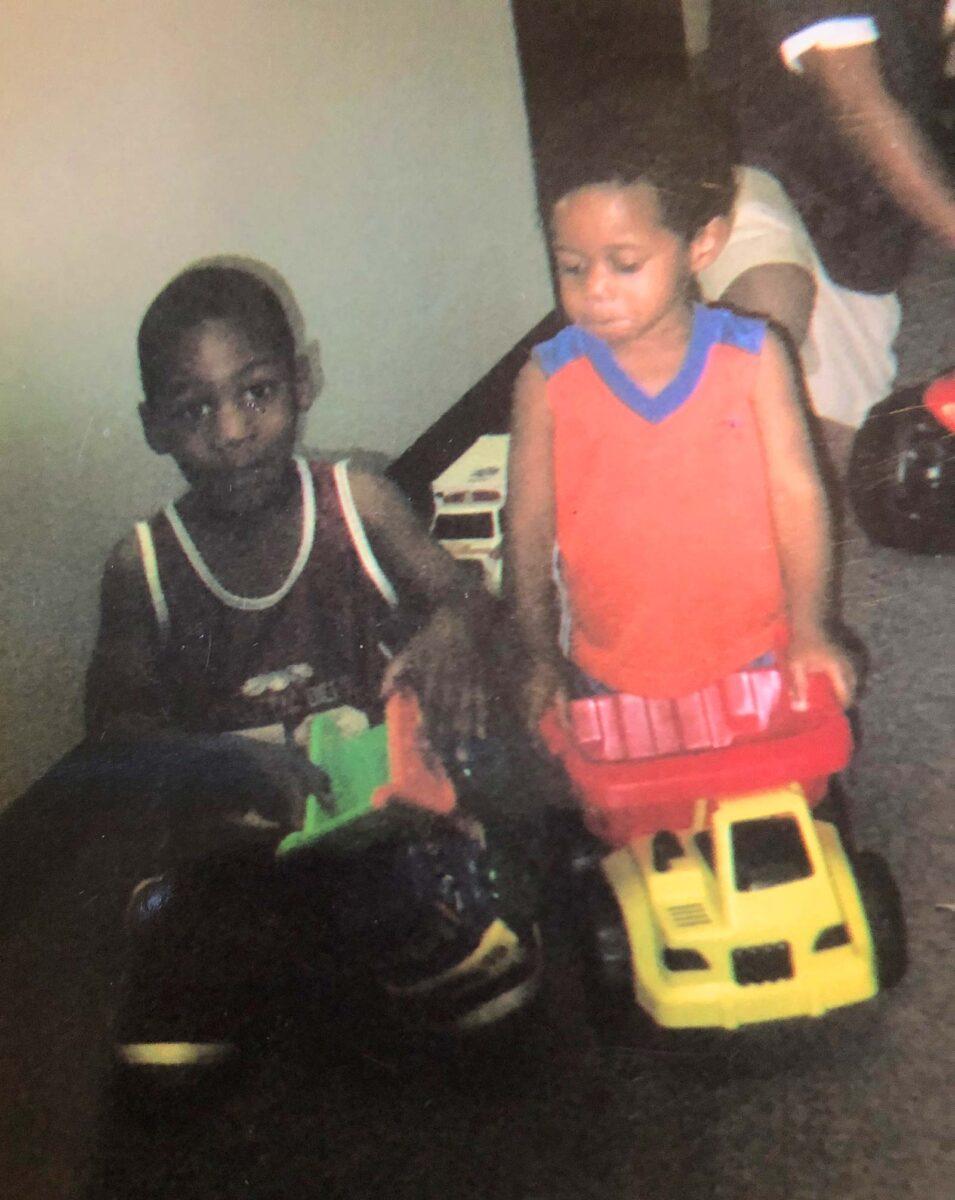

Nathaniel Davis keeps a framed portrait in his apartment of himself holding Ciara in his lap. He brings out a bag of photos; in one, Devonte and Jeremiah play with toy trucks, Devonte’s big eyes focused on the camera. “They called me Dad,” he said, his eyes brimming with tears. They lived with him in his apartment, and he set up bunk beds in their room. He doesn’t remember them ever using the bunks, though—they preferred to sleep with him, all four piled in his bed. He was devastated when he lost the kids in 2006, after he says CPS caseworkers had reason to believe the kids were being left alone with Sherry, something Nathaniel denies.

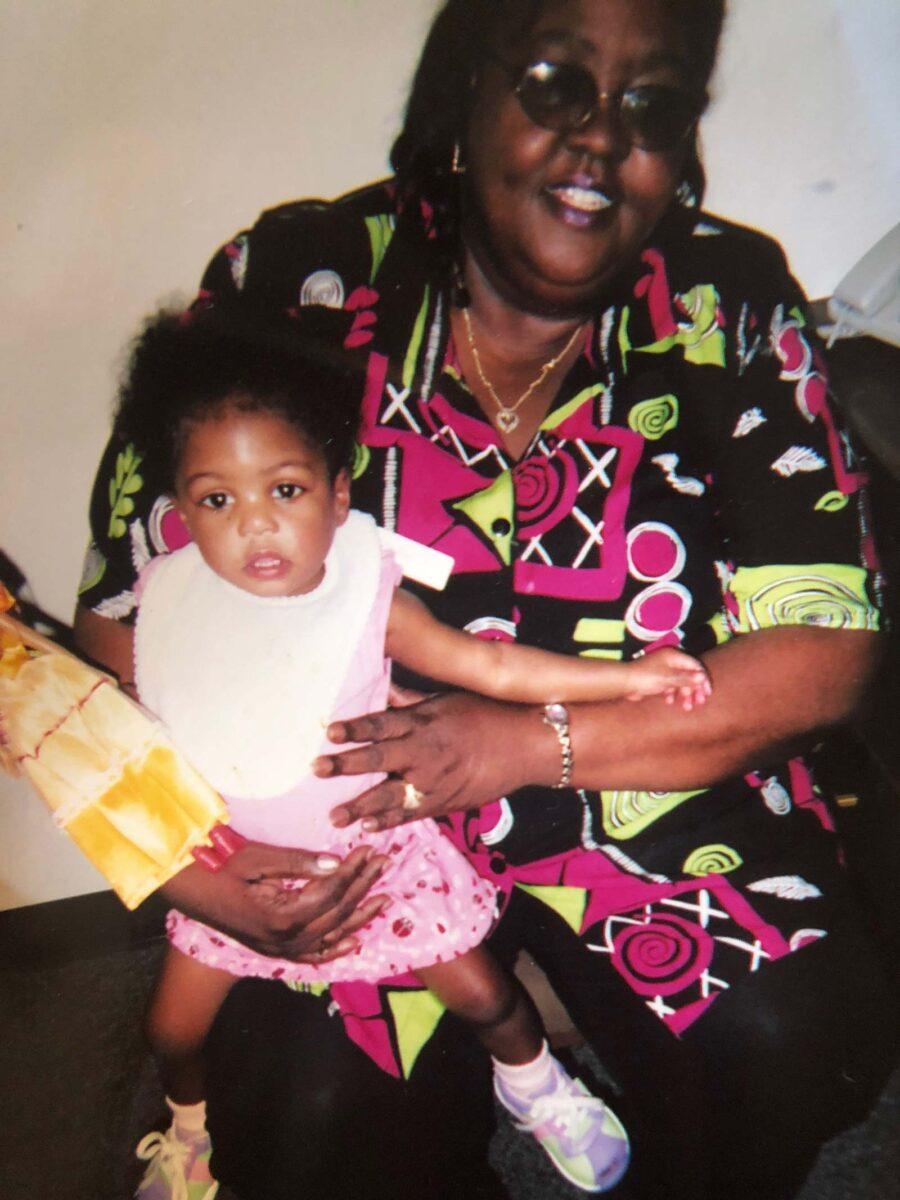

They were sent to live with their paternal aunt, Priscilla Celestine (her brother—Jeremiah and Ciara’s father—was in and out of jail and never obtained custody). The kids all loved to play hide-and-seek with her, she remembers, and they scarfed down chicken nuggets and fish fry.

Priscilla has never forgiven herself for losing the children in December 2006. Employed as a receptionist in a hospital, Priscilla said she moved with her grown daughter and her granddaughter into a five-bedroom apartment so Davis’s children would have more room.

Sherry Davis and Clarence Celestine had agreed to terminate their parental rights. Both say they were told by Clarence’s lawyer at the time, Shonda Jones, that if they terminated their rights, Priscilla would have a better chance at adopting the kids. But that meant they weren’t allowed to contact the children.

She told them, ‘Kiss your mama.’ That was the last time I saw them.

Sherry Davis mother

Davis couldn’t follow that rule. She said she was fixing their dinner at Priscilla’s when a CPS caseworker came by unannounced; Priscilla was not home. The caseworker told Davis to dress the children, who were crying, Davis recalled, and then took them with her on the spot. “She told them, ‘Kiss your mama,’” Davis said. “That was the last time I saw them.”

After the children were removed that day, the family would pool together about $3,000 to appeal the decision and for Priscilla to petition to adopt the four kids; both efforts failed. But by the time Priscilla’s case was finally decided by an appeals court in July 2010, the children had already been adopted by the Harts for more than a year.

Sherry Davis says she had gone through the drug program that was required by authorities after she’d lost custody of the children and remained clean until she heard the news that the kids would be adopted by a couple in Minnesota. “I gave up,” she said, adding that she continued to use cocaine for a year before getting clean eight years ago.

“There are times when kids need to be taken away from their parents, and in this instance, with Sherry, they needed to be,” Jones said. “But I really feel Priscilla was a safe place for them.” While the public will never know every detail in the case files, Jones and other attorneys say what happened in this case fits a broader pattern among child welfare cases in Houston of rushed adoptions, often to the detriment of family members.

“You have people here, loved ones, to take them in, and you take them away,” Priscilla said. “Snatching people’s children for nothing—for their rules. I was looking for a little more mercy from them.”

In 2014, Nathaniel Davis got custody of Dontay, the three children’s older sibling, who was living in a boys home and was not adopted by the Harts. Dontay was arrested for a robbery in October 2015; he’s serving three years in the Lewis Unit, a prison in Woodville, Texas. When he was sent there, Nathaniel said he told Dontay, “‘When you get out, we are going to get on the internet and find your brothers and sister.’ I said, ‘Before I die, I’m going to get all of us together’—intending to do that.”

“Some kids, when they [are] grown, come back and say, ‘Why didn’t you fight for us?’” he added. “And I swear I did. We all did.”

A ‘pay-to-play system’

Each time a CPS case is heard in the Harris County juvenile courts, the bench is crowded with attorneys, most of whom are appointed by the courts. An ad litem attorney is appointed to argue for the child’s wishes. Another attorney represents CPS, and another (or several, depending on the case) represents the parents. Since many parents can’t afford private attorneys, their attorneys are often appointed as well.

For a child to be adopted in Texas, parental rights must be terminated and all legal parties “must agree on moving forward with an adoptive family to make sure the family is the best fit for the child,” Texas CPS spokesperson Tejal Patel said in an email. “A judge must sign off on the adoption as well.”

Because Texas seals its CPS and adoption records, it’s unclear which Harris County judge signed the order for Devonte, Jeremiah, and Ciara’s adoptions by the Harts, but the 313th Judicial District Court oversaw at least two cases involving the children. The presiding judge for that court was Patrick Shelton. As the head of the 313th, Shelton appointed and oversaw an associate judge, Robert Molder, and set the tone and the pace of the court.

Shelton signed the order to terminate the children’s biological parents’ rights in 2006. And Molder ruled on the aunt’s petition for adoption in 2008; a panel of judges ruled on her appeal.

The 313th Judicial District Court is one of three juvenile courts that handle the majority of CPS cases in Harris County; the 314th and 315th Judicial District Courts also serve this purpose. And the 313th and 314th have engaged in practices that have been criticized as questionable at best. The 313th first came under public scrutiny in the late 1990s, when the Houston Press reported that Shelton had a habit of appointing attorneys who had donated to his political campaigns to represent children in CPS and juvenile delinquency cases. Under a 2001 law called the Texas Fair Defense Act, attorneys who are appointed are supposed to be chosen at random from a list of qualified people, but until 2011, that law allowed for judges to develop their own appointment plans.

In 1998, the Houston Press ran a short column about Shelton butting heads with Texas Protective and Regulatory Services, now known as the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services, for appointing attorneys to monitor CPS workers in an effort to speed up adoptions. The child welfare agency accused him of trying to line the pockets of his favored attorneys. Shelton argued at the time that he simply wanted to speed up adoptions so children wouldn’t languish in foster care.

The next year, the same paper reported that Shelton had criticized the English skills of a mother of Mexican descent and was “running a budget legal service” out of his courtroom by asking families, some of whom qualified for free legal representation, to come to court with $150 to get matched with one of the judge’s favored attorneys.

“Anybody who speaks to you at any length about Shelton will tell you the man is obsessed with efficiency, with speed,” Elmer Bailey, who was Harris County’s juvenile probation director, told the Houston Press at the time. “Instead of resetting the case, as other judges do, he says, ‘Well, we’re going to hear the case. I’ll get you an attorney, we’re gonna get you in the court, off the docket, no more missed time, no more fooling around, we’re going to do disposition, and we’ll just work this attorney money out in this variety of ways.’”

Judge Shelton disputed the accusations. “I don’t choose who shows up in court. Any attorney who has a license can practice in the court,” he said in the 1999 article. “If somebody shows up in court and tells me they want to do a court appointment, we consider everybody. It is not a closed show.”

If the court wanted to adopt a kid out but you objected to it, you’re slowing it down, you’re the obstructionist.

JoAnne Musick Assistant District Attorney

Yet the allegations against him persisted. A 2008 report in the Houston Chronicle noted that more than 90 percent of Shelton’s campaign contributions between 2005 and 2008, as well as those to Judge John Phillips in the 314th Judicial District Court, came from attorneys they appointed. “There was very much a pay-to-play system,” Assistant District Attorney JoAnne Musick, who was assigned to Shelton’s court as a prosecutor in the late ’90s and early 2000s, told The Appeal. “If you didn’t work your cases out fast enough or get the solution the court wanted—if the court wanted to adopt a kid out but you objected to it, you’re slowing it down, you’re the obstructionist. Rather than look at it like the attorney may be doing their job and the placement might not be appropriate.”

Two Houston Chronicle columns that focused on cases Shelton heard right before he left the bench in 2010 described situations that were strikingly similar to Priscilla’s failed adoption attempt. In one, the aunt and uncle of a 14-year-old girl who had twins were trying to adopt their niece and her babies. Shelton was in the process of fast-tracking an adoption of the twins to foster parents amid protests from their family members before a Texas state senator stepped in. The second case involved a mentally disabled girl and her baby; her aunt and uncle also wanted to adopt both their niece and her child, but weren’t even given a home study before Shelton approved the adoption of the baby by foster parents.

“They think they are doing a service,” said Shonda Jones, Priscilla’s lawyer. “People become desensitized, it becomes like an assembly line, but you get this feeling that they think, ‘You shouldn’t have had any of these kids.’”

Robert Molder, who is now retired, declined to comment on the case. When reached by phone, Patrick Shelton, also retired, called the allegations regarding his appointments “totally inaccurate.” He said he didn’t remember Davis’s children specifically. “We had hundreds of adoptions done in every court that deals with these cases,” he told The Appeal. But he was aware of some details of the Harts’ alleged abuse and their deaths, and spoke about some of the decisions made in the case.

Shelton said that CPS no doubt tried to place the children locally, and then in-state, before pursuing out-of-state adoption. “There are a number of children that are posted on a nationwide network, particularly if there are groups of children, that’s sometimes what it takes,” Shelton said. “Minnesota has been very helpful overall in providing folks who have an interest in adoptions.”

As for how the Harts were allowed to adopt Devonte, Jeremiah, and Ciara after an allegation of abuse had already been made against them, Shelton said that the lack of criminal charges in that case would most likely have made it pass under the radar of officials in Texas. “I guess that’s the equivalent of cases that are unsubstantiated. Unless there’s a criminal charge, what can you do?” Shelton said. “Believe it or not, kids get bruises that do not get beat.”

Shelton denies reports that he, or his associate judge, favored nonrelative adoptions over placements with family members. “You’re trying to say, wait a second, you’ve got to have perfect crystal-ball knowledge of how somebody’s gonna fare in Minnesota and second-guess yourself on everything you did,” Shelton said, his voice agitated. “We have been disappointed by so many relatives before, that act like kids are the property of the parents, and they’ll say what they need to say just to get the kids back to the parent … and it’s not just the parent, it’s whoever else in their life, typically a crummy boyfriend, especially when drugs are on the scene.”

New rules, ‘same incestuous house’

In 2015, the Texas legislature passed a law aimed at reforming the free-rein system of ad litem appointments throughout Texas. SB 1876 requires judges to appoint attorneys using a randomized wheel system. State Senator Judith Zaffirini, of Laredo, said she introduced the bill in response to actions by former Webb County Court at Law Judge Jesus Garza, who was later indicted for soliciting a $3,000 loan from an attorney in exchange for appointing her to represent a wealthy client in an estate dispute. The charge was dropped with the condition of Garza’s resignation from the Texas bar. But while Garza’s situation was especially disturbing, there was troubling behavior statewide, Zaffirini said. “The more we looked at it, the bigger the problem seemed to be.”

Although the laws have changed, some aspects of the Harris County District Courts have stayed the same. Shelton is gone, but he’s been replaced by another player in the parental rights termination case that led to Devonte, Jeremiah, and Ciara’s adoption by the Hart couple. Glenn Devlin, an attorney at the time, was appointed to search for two of the children’s fathers, and is now the presiding judge of the 313th District court. Devlin was also the former law partner and campaign treasurer of the sitting judge in the next court, John Phillips of the 314th, and reportedly an old favorite of Shelton’s for appointments.

In 1999, the Houston Press reported that Devlin gave $9,990 in contributions to Shelton’s campaign in less than a year between 1997 and 1998, and received $42,008 for 456 case appointments in Shelton’s court over that same period. “It’s still the same incestuous house,” says Musick, the assistant district attorney, noting that many of the same attorneys and judges are still trying and hearing CPS cases. “The practices have somewhat changed because they’ve been exposed. But it’s still involving the same people.”

Julie Ketterman, an attorney who has represented parents in Harris County CPS cases for nearly two decades, says although the wheel system was meant to reform the courts, some problems persist. Ketterman said, in her experience, court-appointed lawyers often don’t fight for their clients. “They’ll have 15-minute trials where parents’ rights are getting terminated and you see a young mom who walks out and doesn’t even know what happened,” she said.

Multiple calls and emails to the court manager of the Harris County Juvenile Courts, whose duties include maintaining the current system for appointing attorneys, were unanswered. But even if these practices ultimately improve, the reforms will come too late for Devonte, Jeremiah, and Ciara, and for countless other children who were shuffled through the courts. “These are lives, these are families,” Ketterman said. “They do what they want to do; kids are separated from moms and dads and grandparents forever.”